Ploughing

It is pertinent to point out that the essence of ploughing is to prepare a seedbed for a planned crop. It is important to understand that what we in the developed world are only too familiar with as agricultural practice was developed in the NW of Europe, stemming from the introduction of the mould board plough and widely used over the last two centuries. This particular way of agriculture is, remarkably, still confined to a small part of the world's agriculture and has in fact proved a disaster in several contexts.

The action of the mould board in turning over or inverting a complete furrow differs entirely from that of the ard, a tool which persisted for most of agricultural civilisation and is still in use today. Indeed it could be said that the action of the modern direct drills closely mimics that of the ard. Results from both experience and experiment, using the mould board plough, show that any effects produced are not universally necessary and hence show why the ard has proved effective for so long, with certain limitations. The following discussion highlights the most important points.

Properly used the mould board plough fully inverts a furrow, leaving the surface bare. At the same time it can be used to bury surface manure or turn in relatively immobile fertilisers, such as marl and lime (known to have long standing use) and potash and phosphates.

In terms of germination of a crop, the disruption of the local weed community by burying annual surface weeds and breaking the root systems of perennial weeds is clear. However, early work at Butser (Reynolds 1979) showed that Einkorn, in particular, competes vigorously with weeds, so that full disruption of the weed community is not crucial to adequate (as opposed to maximal) cropping. A similar point applies to the effects of Hoeing, later in the growing cycle.

This need for distributing manure and fertiliser through a greater or lesser depth will vary on different soils. Where trying to work land with a very acid subsoil, deep penetration of marl or lime may be of benefit. However on soils into which roots can penetrate several feet quite readily, as on agricultural land of first choice (and readily available to early civilisations, until population pressures forced the use of more marginal land or more difficult, heavier or more poorly drained soils), then the necessity of deeper burial is minimal.

As early as 1961, Russell was writing:

"There is, however, a very extensive body of experience and of experimental results that have shown deep ploughing to have no beneficial effect on the crop, and that, for as far as crop yields are concerned, ploughing depths of 4 inches appear to be quite satisfactory, though this is probably only true if the land is free from weeds."

It could be argued that this must have been so or man would have had to create a better approach than the ard much earlier than is the case.

This depth of 4 inches (100 mm) is well within the compass of most known types of ard on most soils. It is recognised that continual ploughing to the same depth can lead to pan formation (see Soils). This may be one explanation why on chalk subsoils, in particular, deep score marks have been found during excavation. It is possible, or even probable, that these represent a special technique to break a pan up. The exact way of doing this has not been convincingly demonstrated at Butser, as it was found that the tips of the ards used tended simply to dig in and resist further movement. It is possible the score marks actually represent this undesirable outcome of inexact use of the tool or failure to identify the particular tool used by early man. Reynolds, in company with Fowler, saw in NW Spain, in the late 1970's, a massive ard "el cambelo", being used to rip out the roots of shrubs and break new ground. Shown below, this appeared likely to be able to make such scores in the sub-

In the section on soils (link above), some comments were made about high power, deep ploughing to remediate some soils. This is not universally the case. Deep ploughing to, say, 15-

Returning to the consequences of the essentially bare surface left by the European mould board plough, it is necessary to see how different climates have an impact. A bare surface is very susceptible to erosion, which is not too critical in moister, cooler climates but is little short of a disaster in the humid tropics, with torrential rains, or in wind blown arid areas.

Thus, alternative routes to seed bed preparation, in the absence of the mould board, centre on other ways to control weeds.

In reality, the ard meets this need, since it undercuts existing weeds and plants, leaving the roots loosened so that the weeds dry and die. This is accentuated by ploughing at just the right time. Since much of the earliest agricultural activity arose in areas where there were adequate hotter, drier periods, this could readily be achieved. At the same time erosion is minimised, since the drying plants and their roots help stabilise the soil, and they also act as a mulch to retain maximum moisture.

It is then no accident that the mould board was developed in NW Europe, where such conditions do not often coincide with the period before the growing season starts.

Similar criteria again apply to Hoeing.

It is also worth repeating that ploughing and hoeing modify, but only in a limited way, the underlying character of two of the uncontrolled factors (Soil and Arable Plant Communities).

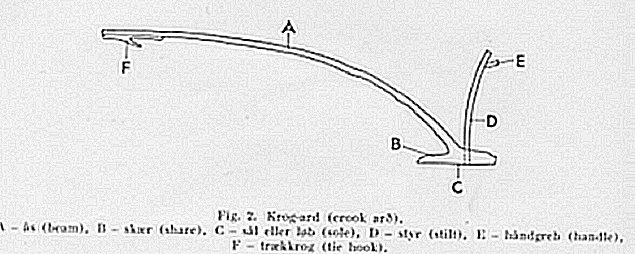

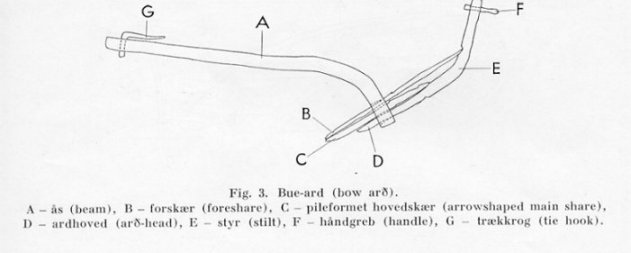

P.V. Glob's survey (1951) is still the definitive publication on ard types. His work is based on excavated finds, mainly from bogs and marshes. He follows Norwegian and Swedish nomenclature in reserving the term plough for implements with a mould board. The term ard is used for symmetrical implements. He divides ards into crook ards, with a crook and horizontal sole and bow ards which terminate with an inclined share. There are also types known as sole ards and stave ards. Prehistoric sole ards were not known in Scandinavia (at least, in 1951), though depicted on Grecian vases. Stave ards are only known from Scandinavian rock carvings.

The following two figures from Glob (1951) illustrate the main features of the crook and bow ards.

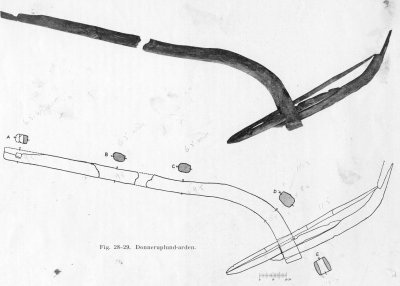

The best example of a bow ard to survive was found at Donnerupland and is illustrated below.

This was reconstructed for trials at the original Little Butser site, as it is similar to the less complete remains of two ards found in Scotland. The image on the right shows the reconstructed Donnerupland ard. A replica ‘Roman’ ard which has metal wings either side of a more pointed share and stirred the soil to a greater extent was also made and used extensively is shown below.

Students who have absorbed the lessons of experimental design requirements will appreciate that a full, comparative, side by side trial of the ard against a modern plough would be an irrelevance. The fact that the ard has persisted proves its utility. The trials at Butser were to gain an insight into how it might be used and, amongst other things, to test whether this particular ard could reproduce sub-

Fuller details of the relevance of various ards, in use, are given in the paper "Deadstock and Livestock" (Mercer 1981).

Footnote

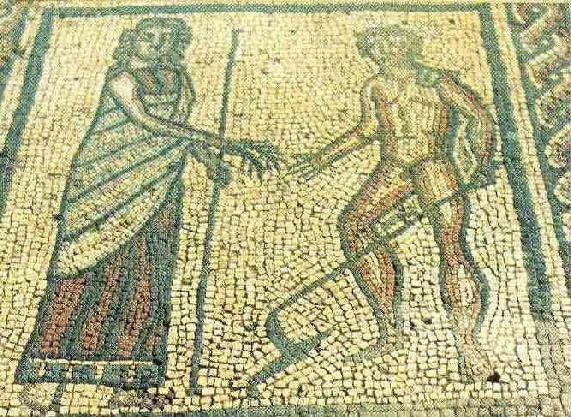

For those interested in the popular beliefs [or myths] of the Romans, the mosaic element below shows Ceres with Triptolemus, holding the plough that he was said to have invented, thereby leading to the introduction of agriculture. One does, however, need to put this in the context of the archaeological evidence for agriculture emerging long before the Romans, as we know them, w ere even thought of !!

ere even thought of !!

This is part of an assemblage of much under-

There is a website to visit : www.bradingromanvilla.org.uk

References

Glob P.V. "Ard og Plov o Nordens Oldtid" Jysk Arkaeologisk Selskabs Skrifter Bind 1 Universitetsforlaget I Aarhus (Denmark) 1951 [with English precis pp 109-

Mercer, Roger (ed.) "Farming Practice in British Prehistory" Edinburgh University Press 1981 [Based on a symposium at Edinburgh University in November 1980].

Reynolds, Peter J. "Iron Age Farm: The Butser Experiment" British Museum Publications 1979.

Russell E Walter "Soil Conditions and Plant Growth" Longmans 1961 (9th ed.) [the first seven editions of this text were written by Sir E John Russell formerly Director of the Rothamsted Experimental Station UK]

For more images of ploughs and ploughing click here